Cathode Materials

Cathodes are where battery performance goes to live or die, where some people immediately get overwhelmed, slide decks tend to get optimistic and lifetime data quietly disappears.

They’re the biggest cost driver in a lithium-ion cell, the main determinant of energy density, and the place where companies most often fall in love with the wrong thing.

Let’s get into it.

Cathodes

The cathode is the battery’s positive electrode and biggest cost driver: around 50% of the cell price. Daqus Energy has a great infographic on the cost of the cathode. This is why cathode selection is rarely a purely scientific decision, it is a supply chain, warranty, and geopolitical decision wearing a lab coat.

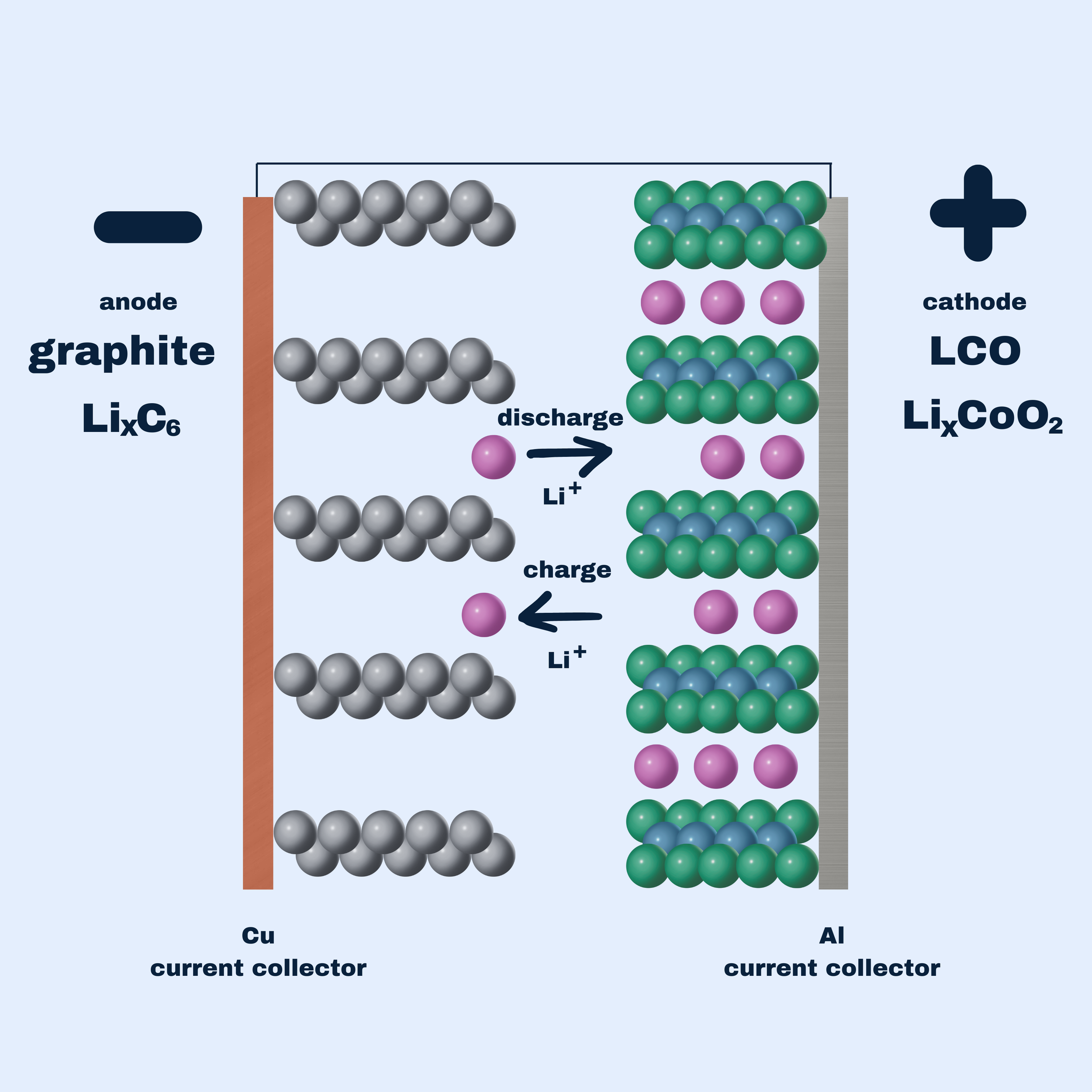

In most lithium-ion batteries both the cathode and the anode are intercalation hosts that lithium-ions can reversibly move in and out of, with lithium-ions and electrons moving towards the negative electrode (“anode”) during charge, and towards the positive electrode (“cathode”) during discharge, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A lithium-ion battery with LCO as the cathode and graphite as the anode.

When choosing a cathode, the relevant question is not “which chemistry is best,” but which tradeoffs matter most for the application.

Changing the cathode chemistry doesn’t just change energy density. It changes thermal management, pack design, warranty risk, supplier exposure, and even recycling economics.

What matters when choosing a cathode:

Gravimetric & volumetric energy density (Wh/kg, Wh/L)

Wh/kg tells you how light a pack can be

Wh/L tells you how big it has to be — and how much thermal, structural, and packaging overhead you inherit

Cycle life & calendar life (how many cycles before capacity falls to e.g. 80%)

Power / rate capability (C-rate performance)

Safety / thermal stability (thermal runaway, oxygen release)

Cost & supply chain / critical materials (cobalt, nickel content; geographic concentration)

Scalability and manufacturability (synthesis complexity, coating requirements)

Optimizing one of these almost always makes at least one other worse. Anyone claiming otherwise is either early in development or early in fundraising.

The History

Lithium-ion cathode material LiCoO2 (LCO) was the first commercially available layered transition metal oxide cathode material. LCO was discovered by John Goodenough in 1980, commercialized by SONY, and is still used in a large majority of lithium-ion batteries today. LCO’s low stability at high states of charge (SOC) combined with the high cost of cobalt has led to a partial substitution to other transition metals, like Ni and Mn, resulting in LiNiO2 (LNO), LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 (NCA), and LiNixMnyCo1−x−yO2 (NMC) cathode materials. NMC having equal amounts of nickel, manganese, and cobalt gives the formula: LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2 and is referred to as NMC111. The most commonly used lithium-ion battery cathode materials are displayed in Table 1. The table below is not a ranking. It is a map of tradeoffs that the industry keeps relearning.

The path from Goodenough's 1980 discovery of LCO to commercial lithium-ion batteries required more than cathode chemistry alone. Asahi Kasei's work on compatible carbon anodes and Sony's manufacturing expertise in precision film coating—borrowed from their magnetic tape division—enabled the first commercial cells in 1991. This integration of materials science with scalable manufacturing remains a central challenge for newer cathode chemistries today. The chemistry has evolved. The scaling problem has not.

| Cathode | Structure | Nominal Voltage (V) | Specific Capacity (mAh g−1) | Key Strengths | Main Drawbacks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCOLiCoO2 | Layered oxide | 3.9 | 150 | Mature technology, high voltage | High Co cost/toxicity; thermal issues at high SOC | 1, 2 14 |

| NMC LiNixMnyCozO2 e.g. NMC811, NMC111 | Layered oxide | 3.8 (811) | 220 (811) | High gravimetric energy, compositional tunability | Ni-related structural instability; degradation at high V | 3, 4 13 |

| NCALiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 | Layered oxide | 3.8 | 200 | High energy density | Cost (Co/Ni); thermal sensitivity | [4, 13] |

| LFPLiFePO4 | Olivine | 3.2 | 150 | Excellent safety and cycle life; low cost; Co-free | Lower voltage and volumetric energy density | 5, 6 12 |

| LMFPLiMnxFe1−xPO4 | Olivine | 3.8 | 145 | Co-free; olivine stability; higher energy density than LFP | Sluggish Mn2+/Mn3+ kinetics; density–rate tradeoff | 7, 12 13 |

| LMOLiMn2O4 | Spinel | 4.0 | 120 | High power, low cost, Co-free | Mn dissolution; moderate cycle life | 8, 9 12 |

| LNMOLiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 | High-voltage spinel | 4.7 | 130 | High power; Co-free; 3D Li diffusion | Electrolyte oxidation; HF attack at high V | 10, 4 13 |

| Li-rich layered oxides (LRLO) Li1+xM1−xO2 | Li-excess layered; anionic redox | 3.5–4.8 | 250 | Very high capacity; low Co | Voltage decay; oxygen loss; first-cycle inefficiency | 11, 4 13 |

Lithium-ion cathode materials can be broadly classified by their crystal structure: layered oxides, spinels, and olivine polyanions. Each structure offers distinct electrochemical characteristics and tradeoffs.

Layered oxide cathodes: Layered transition-metal oxides (LCO, NMC, NCA, and Li-rich variants) dominate applications where energy density is the primary driver- consumer electronics and EVs. Within this family, industry has steadily shifted toward Ni-rich compositions to raise capacity and reduce cobalt dependence.

This shift is not free. Ni-rich cathodes get their extra capacity by asking nickel to do more of the electrochemical work — and nickel becomes increasingly unstable when pushed to high oxidation states. Ni-rich layered oxides are more prone to surface reconstruction, transition-metal dissolution, and interfacial degradation at high voltages, all of which accelerate capacity fade and raise thermal-management demands.

As a result, Ni-rich cathodes often require tighter materials control, surface coatings, electrolyte additives, and more conservative operating windows to achieve acceptable lifetime.

Spinel cathodes (LMO and LNMO) provide high power and excellent rate capability due to their three-dimensional lithium diffusion pathways and are cobalt-free, reducing cost and supply chain concerns. LNMO operates at a notably high voltage (~4.7 V vs Li), but this creates challenges with electrolyte oxidation. LMO suffers from manganese dissolution, limiting cycle life.

Olivine polyanion cathodes (LFP and LMFP) offer superior thermal stability, long cycle life, and low cost due to abundant iron and phosphate. Their lower intrinsic electronic and ionic conductivities have been addressed through nanostructuring and carbon coating, enabling competitive rate performance. The tradeoff is lower operating voltage and energy density compared to layered oxides.

The specific contenders:

1) NMC: the workhorse, trending Ni-rich

NMC is actually a family (NMC111, NMC532, NMC622, NMC811, etc.). Increasing nickel fraction raises capacity but also raises structural/chemical instability. Ni-rich variants (≥80% Ni) are favored for high energy but face faster degradation and tougher thermal management requirements. The extra capacity is real. So is the added complexity required to keep it from self-sabotaging.

Strengths: High energy density (best among commercial oxide cathodes today), good compromise between power and energy.

Weaknesses: Structural instability during deep delithiation, surface reconstruction, transition-metal dissolution, and sensitivity to high-voltage charging, all of which accelerate capacity fade. Improving coatings, dopants, and electrolyte additives is active research.

2) NCA:

Comparable to NMC in energy density, often used by some EV makers. It offers high energy but can be less forgiving than NMC in abuse conditions.

Pros/cons: Similar tradeoffs to Ni-rich NMC: very good energy, more demanding management and materials control. Recent literature treats NCA alongside Ni-rich NMC when discussing high-energy oxide challenges.

3) LFP:

Iron-based olivine structure with much better thermal stability and long cycle life but lower nominal voltage (~3.2 V) and lower energy density than NMC/NCA. LFP’s resurgence is not a chemistry breakthrough so much as a systems-level optimization. While its lower voltage and volumetric energy density necessitate larger packs, its superior thermal stability, long cycle life, and reduced reliance on critical materials simplify pack design, thermal management, and warranty risk. For many manufacturers, these advantages outweigh the penalties in size and mass. Recent market analyses and comparative studies increasingly frame LFP adoption as a cost- and risk-driven decision rather than a performance compromise. LFP’s resurgence reflects respect for physical limits, not a breakthrough in chemistry.

Strengths: Exceptional safety, long cycle life, lower cost (no cobalt or nickel), and robust calendar life. These attributes have driven adoption in many short/medium-range EVs and grid/storage systems. Recent comparative studies and market analyses highlight LFP’s strong cost and safety position.

Weaknesses: Lower volumetric energy density means larger packs for the same range. Lower recyclability economics (less valuable recovered metals) has been noted as a lifecycle consideration.

4) Li-rich layered oxides (LRLO): Also called LMR (for Lithium Manganese-Rich batteries)

These Mn-rich, Li-excess layered materials can deliver much higher specific capacities via activation of anionic (oxygen) redox — promising for next-generation high-energy cathodes.

Strengths: High theoretical and practical capacity, lower reliance on cobalt. Recent high-profile papers show structural engineering can reduce the early irreversible changes that previously plagued these materials.

Weaknesses: Voltage decay and capacity fade linked to structural evolution and oxygen release are still major problems; mitigating them is an active research area (surface reconstruction control, pre-activation, coatings).

5) Spinels (LMO) and high-voltage LNMO:

Spinels are valued for excellent power (high rate) but moderate energy density; LNMO targets higher voltage (~4.7 V) and could be cobalt-free high-power cathode but needs electrolytes/additives that survive the high voltage.

Pros/cons: Good rate performance, lower cobalt; but suffer from Mn dissolution and electrolyte oxidation at high voltage. Research focuses on electrolyte/cell-level strategies. (See reviews of high-voltage oxides.)

Manufacturing the Future

The path from John Goodenough’s discovery of LiCoO₂ in 1980 to commercial lithium-ion batteries required far more than chemistry. Compatible carbon anodes, precision coating techniques, and scalable manufacturing, notably developed at Sony, enabled the first commercial cells in 1991. That integration challenge remains the same today.

Many emerging cathode materials: including Li-rich layered oxides and high-voltage spinels, demonstrate impressive performance in laboratory cells. However, translating these gains into commercial products requires overcoming challenges in electrolyte stability, first-cycle efficiency, formation protocols, and long-term structural evolution. This gap between laboratory promise and manufacturable reality remains one of the central bottlenecks in cathode innovation. Most cathode failures happen not at the coin cell, but at the coating line.

Takeaway:

No single “best” cathode exists. Choice depends on the target metric mix (energy vs cost vs safety).

Industry split: High-energy Ni-rich oxides for range/performance vs LFP for cost/safety/durability.

Every chemistry choice is a business decision pretending to be a materials decision.

References

R. Konar et al., Energy Storage Materials, 2023 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2023.103001

Fang et al., Journal of Electrochemistry, 2024 https://doi.org/10.61558/2993-074X.3445

Z. Wu et al., Nano Energy, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2024.109620

I. T. Adebanjo et al., Energy Advances, 2025 https://doi.org/10.1039/D5YA00065C

Z. Chai et al., Scientific Reports, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58891-1

G. Ji et al., Nature Communications, 2023 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36197-6

S. Reed et al., Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1039/D4TA03438D

U. Pal, Batteries & Supercaps, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1002/batt.202400072

S. B. Chikkannanavar et al., Journal of Power Sources, 2014 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.09.052

S. Choi et al., ACS Omega, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c09101

H. Liu et al., Nature Communications, 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54312-z

J. B. Goodenough and K. S. Park, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2013 https://doi.org/10.1021/ja3091438

A. Manthiram, Nature Communications, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15550-6

G. E. Blomgren, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0251701jes